Author: Kiley Price | November 18, 2021 | Lessons Learned

Half of “irrecoverable carbon” in just 3.3 percent of land

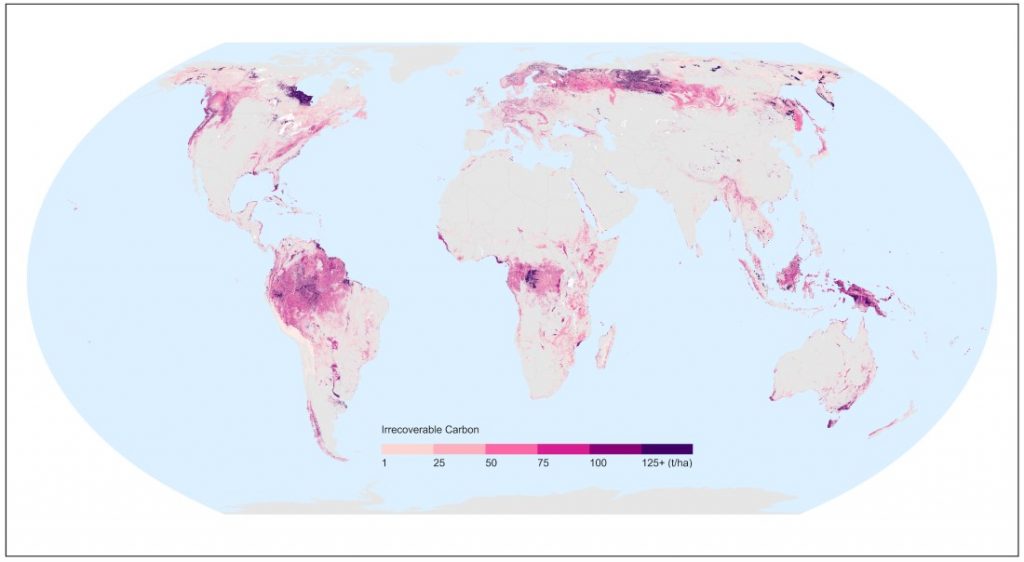

Nature’s stashes of climate-warming carbon are packed into a small percentage of Earth’s lands, finds a new study that pinpoints the ecosystems humanity must protect to avert a climate disaster.

The study, published in the journal Nature Sustainability, found that half of Earth’s “irrecoverable carbon” — defined as carbon that, if emitted into the atmosphere, could not be restored by 2050 — is located in just 3.3 percentof Earth’s land area. The carbon in these reserves is equivalent to 15 times the global fossil fuel emissions released in 2020.

Most of this carbon is found in peatlands, mangroves and old-growth forests across six continents, the study found. Were these ecosystems to be degraded or destroyed due to human activity, their carbon would be emitted into the atmosphere, effectively preventing humanity from limiting global warming to less than 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit), the benchmark for a “safe” climate set by the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Last year, the study’s authors introduced the concept of irrecoverable carbon in a groundbreaking paper; this new research takes their findings a step further by mapping exactly where this carbon is located around the world — and providing policymakers with the clearest view yet on the areas that most need to be protected.

Released just days after the U.N. COP26 climate talks, the study is well-timed for helping countries ensure that they can meet the climate commitments made in Glasgow.

“We are at a pivotal moment for climate action — the science and the solutions are here, and so is the urgency,” said Monica Noon, a scientist at Conservation International and the study’s lead author.

Small investments, big returns

As world leaders rally around a common goal to protect 30 percent of the planet by 2030, the new irrecoverable carbon map could help governments focus their efforts on the ecosystems that are critical to maintaining a stable climate, Noon says.

The good news: Nearly a quarter of the world’s irrecoverable carbon is already located within protected areas.

Even better: Increasing the amount of land under protection in key areas by just 5.4 percent would keep a whopping 75 percent of Earth’s irrecoverable carbon from being released into the atmosphere, according to the study.

Many of the world’s irrecoverable carbon reserves overlap with places containing high concentrations of biodiversity, which would also benefit from stronger protections.

“Our research shows that protecting a relatively small portion of land can secure the majority of irrecoverable carbon,” Noon said. “Mobilizing resources to conserve these areas can have huge returns for the climate, biodiversity and human well-being. Governments need to be strategic when creating new protected areas, while also strengthening legal protections in existing ones.”

Where is the world’s irrecoverable carbon?

Scientists used the latest data — including an analysis of more than 10,000 forest carbon samples — to understand how soil and biomass can recover greenhouse gases after changes in land use.

They found that irrecoverable carbon spans six of the seven continents, including vast stores in the Amazon, the Congo Basin, the islands of Southeast Asia, Northwestern North America, Southern Chile, Southeastern Australia and New Zealand.

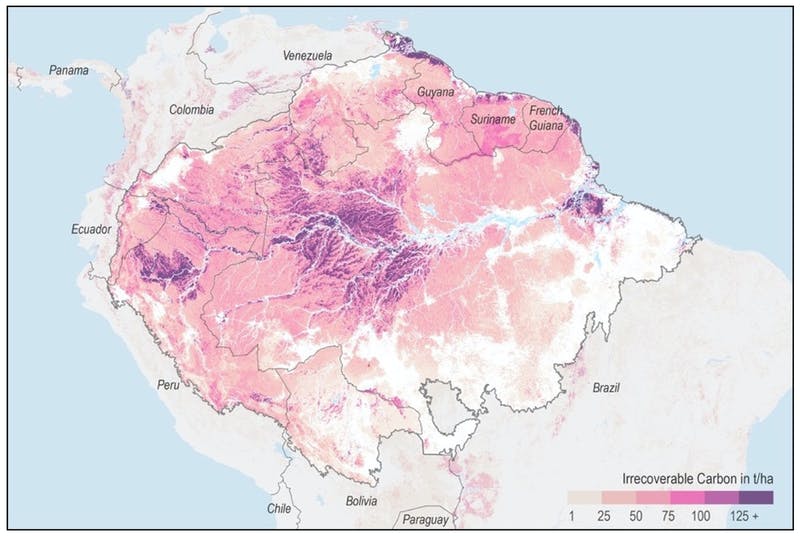

THE AMAZON RAINFOREST

The Amazon is home to 30 million people, including 350 Indigenous and ethnic groups. This rainforest provides habitat for one in 10 known species on the planet and produces nearly a quarter of the world’s freshwater.

It also stores more than 20 percent of all irrecoverable carbon within its trees and soil — more than any other region on Earth.

“Old-growth forests in the Amazon are an extremely high-carbon ecosystems because they’ve been able to sequester carbon over decades or even centuries — and they grow all year round,” said Juan Carlos Ledezma, a Conservation International technical specialist for the Americas programs and co-author on the study.

Some of the Amazon’s largest irrecoverable carbon reserves are located in the Igapó — seasonally flooded forests along the banks of the Amazon River. For up to six months each year, these forests are submerged under several meters of water, which traps carbon in the soil, where it can build up over time.

The problem: A surge in deforestation in recent years is pushing the Amazon closer to a tipping point after which it will lose the ability to generate rainfall, gradually transforming into a dry savanna.

Roughly 15 percent of the Amazon has been deforested so far; the tipping point could occur if a quarter of the forest is lost. At current deforestation rates, that could happen in 10 to 15 years, scientists predict.

“Increased deforestation will accelerate climate change, fueling higher temperatures and lower humidity in the Amazon. This could dry up this rainforest — and release the carbon it holds,” Ledezma explained. “Additionally, dry forests are more likely to catch fire, which would release even more carbon. It’s a dangerous feedback loop, which we must avoid.”

NIGER DELTA MANGROVES

Africa’s Niger Delta boasts the most contiguous stretch of mangroves in the world, rich with wildlife and marine species. However, the real treasure is buried deep in the soil of these swamps.

“A lot of the muck in mangrove forests hasn’t seen the light of day in decades or even centuries. If left undisturbed, the carbon in soil sediments is locked in,” says Conservation International scientist Allie Goldstein, a co-author of the paper. “Mangroves only cover a fraction of Earth’s surface, but what they lack in quantity, they make up for in quality — holding the highest density of irrecoverable carbon of any other ecosystem.”

In the Niger Delta alone, 240 million tons of irrecoverable carbon lie within the dense tangle of trees and soil that make up this coastal forest. Along with these climate benefits, mangroves provide crucial habitats for marine species and can act as a buffer for coastal communities, protecting them from storm surges and rising sea levels.

Despite their importance, mangroves along the Niger Delta face mounting pressure from the extractive industry, which exports 1.41 million barrels of oil from this region each day. In addition to deforestation from the rigs, camps, roads and other infrastructure related to extractive production, oil frequently spills into the mangrove forest, polluting the coastlines and harming the trees.

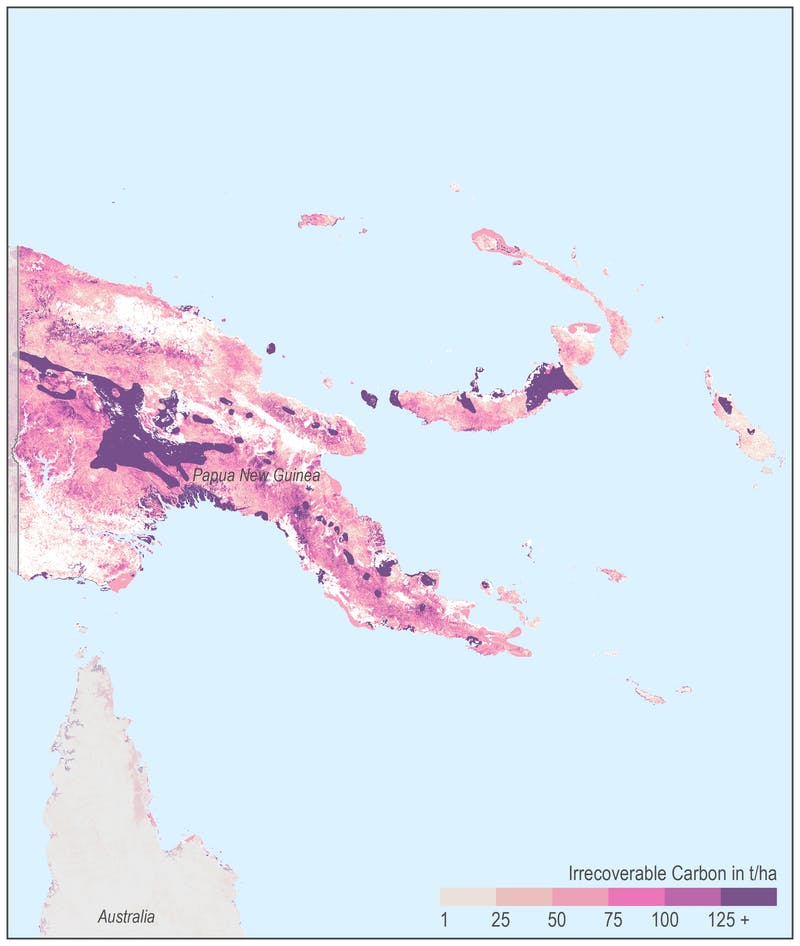

PAPUA NEW GUINEA PEATLANDS

Located in the southwest Pacific, Papua New Guinea holds 3.9 billion metric tons of irrecoverable carbon — making it a “wall-to-wall carbon reserve,” according to Noon.

“The majority of the country’s carbon is stored in its peatlands,” she says. “These wetland ecosystems are made up of decaying waterlogged plants that have accumulated carbon over centuries.”

Globally, peatlands contain more than 39 billion metric tons of irrecoverable carbon, which is built up and locked away in soils. However, just like the flooded forests of the Amazon, these wetlands are extremely vulnerable to changes in moisture.

“Peatlands are climate superstars, but they face a variety of threats that could release the carbon they have stored,” Noon says. “In most cases, peatlands are either drained to transform the land into fertile farming area for oil palm production or extracted as a source of fuel.”

How do we protect irrecoverable carbon?

At least 4 billion metric tons of irrecoverable carbon have been lost due to disturbances such as agriculture or wildfires over the past decade — and deforestation rates continue to rise worldwide.

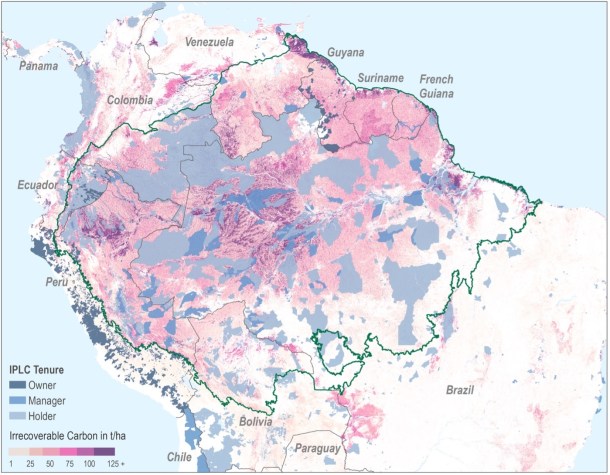

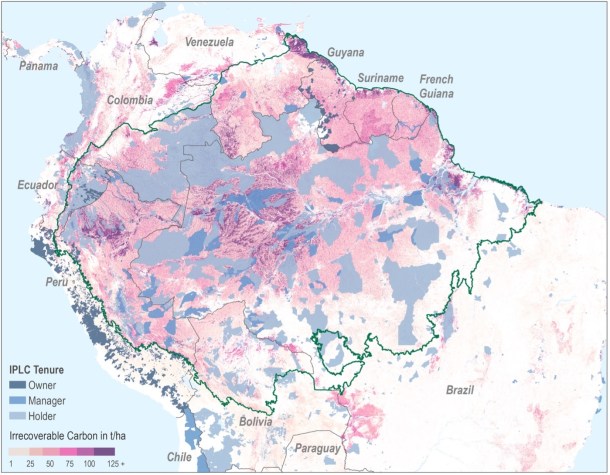

In addition to creating new protected areas, it is essential to recognize the land rights of Indigenous peoples, Noon says.

“Globally, Indigenous peoples are proven to be some of the best stewards of nature; their lands show less species decline and pollution, and more well-managed resources,” she says. “Strengthening Indigenous land rights is a critical step toward protecting the world’s ecosystems and the carbon they store.”

Currently, 47 billion metric tons of irrecoverable carbon — more than a third of the total — are located within government-recognized lands of Indigenous peoples and local communities. The authors say that there is likely even more irrecoverable carbon located on Indigenous and community lands without legal status.

However, being located on Indigenous lands does not always guarantee that irrecoverable carbon is conserved, Ledezma says.

“In the Amazon alone, nearly half of intact forests are located within Indigenous territories, making Indigenous peoples crucial partners in the effort to protect irrecoverable carbon,” he says.

“However, many communities lack the resources and incentives they need to fend off the pressure to turn forests into farms or mining areas. Governments must provide more support for Indigenous communities, strengthen the legal recognition of their lands and formally recognize the crucial role Indigenous peoples play in helping to fight climate change.”

And expanding protection for lands with high concentrations of irrecoverable carbon, as well as supporting Indigenous and community-led conservation measures, is crucial for countries to meet their climate and biodiversity goals, Goldstein adds.

“This is a rare scenario in which we have time to prevent environmental disaster before it happens,” she said.

“This is our generation’s carbon to save, and how we choose to move forward as a global community will determine our climate fate.”

This article originally appeared in Conservation News.

Kiley Price is the staff writer and news editor at Conservation International.

***