Author: David Henry | May 17, 2023 | Initiatives | Location

Haze pollution from peatland and forest fires transcend national borders, negatively impacting ecosystems, human health and economic activities. It also deprives local communities of income from these ecosystems while endangering public health.

Climate change and land-use change are exacerbating this form of air pollution and are likely to cause a 50% increase in the number of wildfires worldwide by the end of the century, according to the UN Environment Programme.

On 30 March 2023, more than 70 representatives from regional fire-management agencies, monitoring organizations, universities, the private sector and ASEAN Peatland Partners attended a workshop on burned area mapping and estimation in Southeast Asia held at the Century Park Hotel in Jakarta, as a step toward developing common guidelines for the region.

The event was part of the Programme on Measurable Action for Haze-Free Sustainable Land Management in Southeast Asia (MAHFSA), a five-year joint initiative between the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). MAHFSA is implemented collaboratively by the ASEAN Secretariat, the Global Environment Centre (GEC), and the Center for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry (CIFOR-ICRAF).

The workshop, co-organized by CIFOR-ICRAF, followed a hybrid format with online participation as well as in-person attendance.

“Burned area mapping and estimation provides important information for improving fire management, to map wildfire risk and urban interface areas, as well as assess different and changing fuel types, fire danger rating, burn severity indices, and seasonal partitioning across landscapes for fire hazard mapping,” said Vong Sok, head of the Environment Division of the ASEAN Secretariat, in his opening address.

The ASEAN region, which consists of 10 member states, experiences wildfires across a range of landscapes. In recent decades, the burning of vegetation and peat to clear land for agriculture has caused significant blazes that emit huge amounts of carbon dioxide and undermine international efforts to curb the greenhouse gases that lead to climate change.

About 90% of these wildfires are anthropogenic, devastating forests and peatlands that store carbon, regulate climate, supply water, support biodiversity and boost livelihoods.

In order to restore land and reduce the number of fire disasters in the future, national authorities need to know exactly where to focus their resources, where illegal burning is taking place, and how to nullify potential hotspots that may emerge.

The concept of a guideline and workshop emerged in 2021 when a stock-taking exercise to identify gaps in knowledge products on fire haze and peatlands in the ASEAN region revealed a lack of information and methodology for estimating and mapping burned areas, according to Michael Brady, a CIFOR-ICRAF scientist who co-manages the MAHFSA Programme.

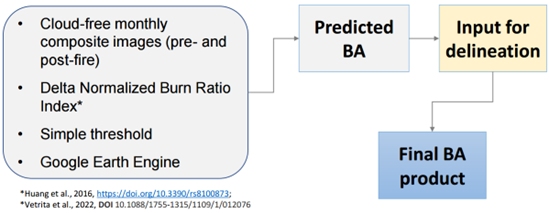

“In many areas, hotspots have been a surrogate for burned area,” Brady said. “Mapping burned areas using hotspots isn’t the best approach. We need to be mapping actual burned area in the post-fire phase to produce accurate results and to know what land-cover types have burned.”

The MAHFSA team aims to build on methodology and operational approaches developed in Indonesia under the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF) and the Research Organization for Aeronautics and Space (ORPA-BRIN), one of the only countries in Southeast Asia that maps burned areas annually, using Landsat and other satellite imagery.

According to the MoEF participants, Indonesia has learned from previous experience with forest and land fires. Technical assistance, such as this workshop, and support from relevant partners and stakeholders are important to deal with such fires. Networking is very important so that best practices, experience and lessons learned can be regularly shared.

Satellite imagery and remote sensing technologies provide vital support for meteorological agencies in countries such as Thailand, the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia, allowing them to publish fire danger rating information and to operate hotspot detection systems.

ASEAN also uses geostationary and polar-orbiting satellites for near real-time imagery of smoke plumes, haze and burn scar detection, providing member states with an early-warning and alert system on transboundary haze, according to Gavin Yeap of the ASEAN Specialised Meteorological Centre (ASMC).

However, hotspot detection is only useful up to a point, as cloud cover and satellite technology limitations can underreport the true number of active fires, according to workshop participants.

This is why the ability to accurately map and estimate burned areas annually is so crucial. With reliable data that can be verified with ground checks, fire managers can improve tools to identify regions with elevated wildfire risk.

The workshop revealed a patchwork approach to burned area mapping and estimation across the region. Most nations called for more training and collaboration to close their knowledge and technology gaps. Speakers included Yoeung Visal of Cambodia’s Ministry of Environment, Nguyen Thanh of Vietnam’s Forest Protection Department, and Surassawadee Phoompanich from Thailand’s Geo-Informatics and Space Technology Development Agency (GISTDA).

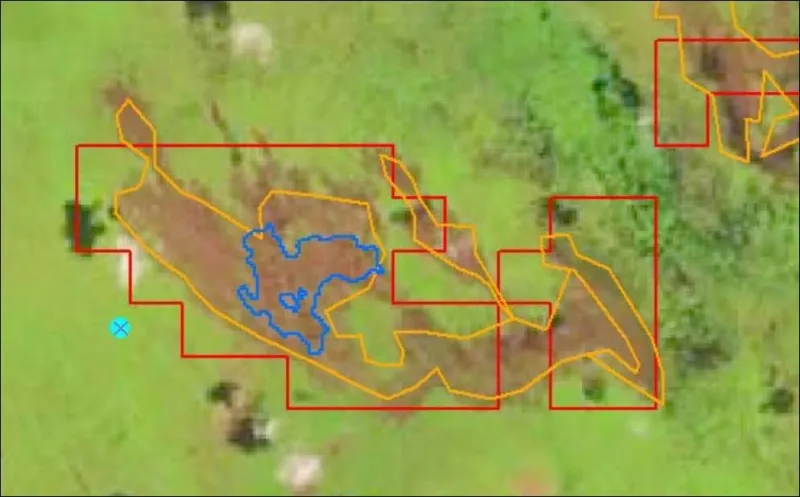

Indonesia is at a more advanced stage with this mapping approach and emerged as a pioneer among the group (Figure 1).

Several participants outlined the evolution of Indonesia’s burned area mapping activities conducted since 2015, when the country began an annual inventory of forest resources. Its results, using Landsat and Sentinel-2 satellite images, are now used for greenhouse gas emission calculations, fire risk maps and spatial reference for determining the location of preventive fire brigade patrols. There are now about 4,000 fire-prone villages mapped in Indonesia.

The country also provides a public interface on hotspots, ground checks and other data, while offering an integrated and interactive forest fire warning system called SPARTAN. Indonesia supports forest and land fire management with SIPP Karhutla, a computer-based system developed to manage data and information on patrol activities. Almost 2,000 national fire brigades (Manggala Agni) are in the field for verification and ground checks.

Burned area information is also used for law enforcement purposes, providing evidence in court cases prosecuting the deliberate use of fire for land clearing.

“Judges are trained to deal with this information – I know because they come to my laboratory to see how it all works,” said Bambang Hero Saharjo, executive director of the Regional Fire Management Resource Center–Southeast Asia. “When they see the satellite data, there is no debate because you can see where the fires come from. When deciding on the punishment, it is all based on scientific evidence.”

Malaysia has also made progress over the past decade, operating a forest fire information system to monitor hotspots and burn-scar areas since 2011. Fire is a major threat to tropical peat swamp forests in Malaysia, particularly the South-East Pahang Peat Swamp Forest. The country now uses SNPP and NOAA-20 satellites to detect hotspots with a high resolution of 375 meters.

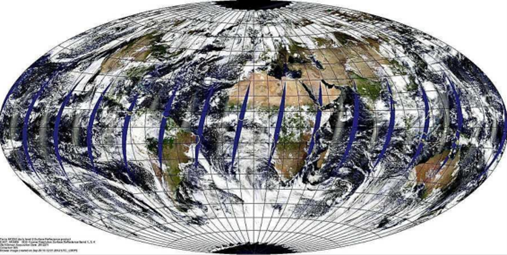

Nevertheless, the standard products available today need to be better understood to interpret the impact of fires accurately, according to Mark Cochrane, a senior scientist at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. Due to challenges from orbital gaps, smoke, clouds, sensor geometry and algorithmic limitations, the optical sensors on satellites such as MODIS and VIIRS fail to collect data over equatorial regions for up to two days per week.

“When you don’t see a fire, it doesn’t mean there is no fire,” Cochrane said. “It could mean that you just didn’t get an image that day (Figure 2). We call it a daily product, but in the equatorial regions, it’s a pseudo-daily product.”

There are also areas with small fires or smoldering fires in peatlands where it is not hot enough – or there is not enough area burning – to release sufficient energy for sensors to pick up. Cochrane showed how VIIRS detections over Southeast Asia on five consecutive days fluctuated from zero to 117 fires, highlighting the need for burned area mapping.

All workshop sessions offered participants the chance to contribute comments through SLIDO polls, which will help with production of the proposed guideline.

Workshop attendees agreed to form a drafting group consisting of Indonesia’s MoEF and ORPA-BRIN, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development of Vietnam (MARD) and the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (MONRE). The MAHFSA Programme and CIFOR-ICRAF will play a coordinating role, and the ASEAN Secretariat will provide guidance.

A draft guideline is expected in December this year, according to workshop participants.